Henry Louis “Hank’’ Aaron turned 80 on Feb. 5, a long life now divided neatly in half by the 40 years building to home run No. 715 and the 40 years spent in service to that epic swing.

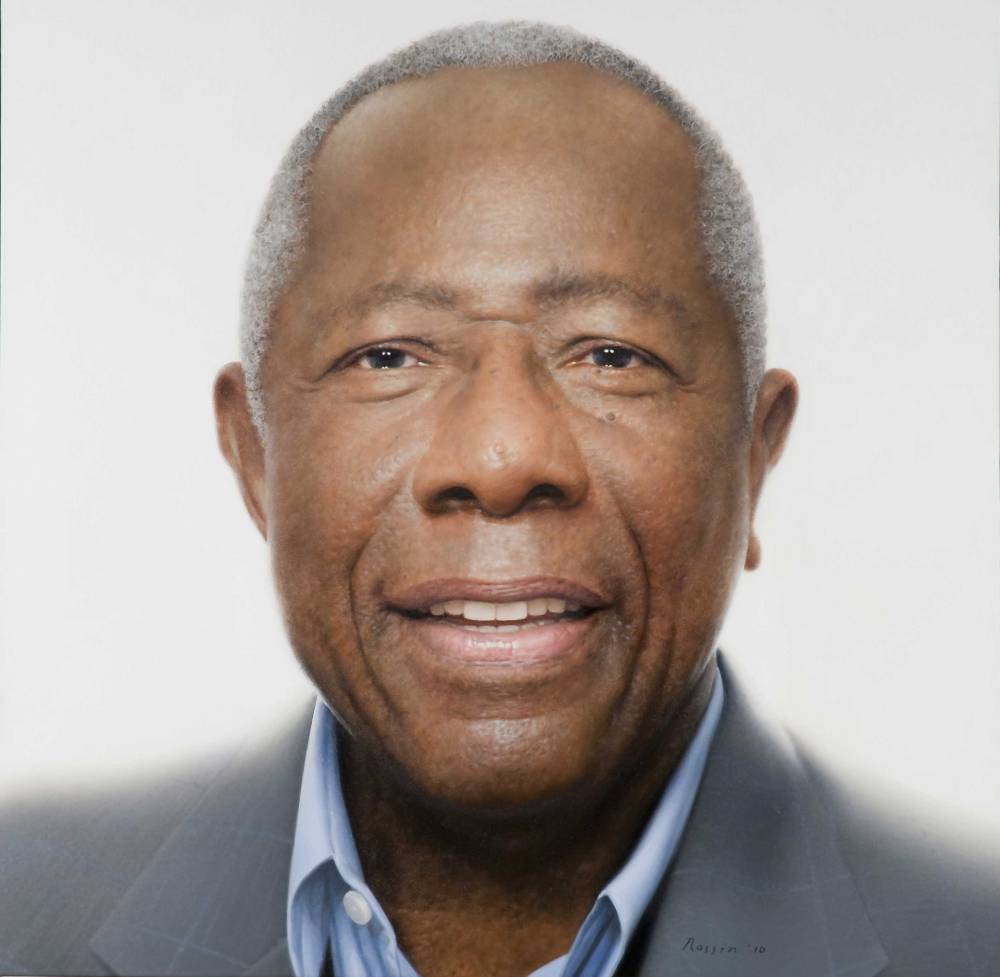

This portrait of Hank Aaron by Atlanta artist Ross Rossin was placed in the Smithsonian earlier this month.

Aaron was honored on Feb. 7 at a dinner thrown by his buddy, Commissioner Bud Selig. On Feb. 8, he and his likeness were celebrated at the Smithsonian’s National Portrait Gallery.

Space in that hall is reserved not only for those who can hit the fastball, but those who have, on a grander scale, influenced a nation’s culture. The Hammer did his share of societal shaping with a 33-ounce piece of sculpted ash.

“Can we tell the story of baseball without Henry Aaron? I don’t think so,” Bethany Bentley, a gallery spokeswoman, said. He’ll keep eclectic company, hanging next to actor Morgan Freeman.

Smithsonian portrait

The artist who did this and another portrait of Aaron to go in the Baseball Hall of Fame, Atlanta’s Ross Rossin, felt it his responsibility to capture “the positive energy that comes from him, the magnetism, the charisma.

“He is more than a sports star; he is an unbelievable human being who represents the time he lived in,” Rossin said. Aaron will be Rossin’s fourth subject displayed at the Smithsonian, along with Freeman, former U.N. ambassador/Atlanta mayor Andrew Young and poet Maya Angelou.

Even someone who has been honored in nearly every conceivable fashion still can be moved by an event of this scale.

“I was there with Andrew Young when they hung his (portrait),” Aaron said this month. “You’re on a different level when you get there. You’ve achieved a lot and somebody upstairs loves you. I don’t know — you feel like somebody special.” Before leaving for D.C., Aaron sat for an interview in the southwest Atlanta home he has been in since 1974. What emerged was another portrait of an octogenarian sporting icon at ease with the sum of his life.

General health

Aaron doesn’t use the tennis court at his home anymore, and in fact jokes about turning it into a garden. Doesn’t fish the five-acre pond out back of the house. But otherwise, “I feel good, I really do,” he said.

Travel can wear him out, but he knows he would feel it all the more had he fully indulged in the pleasures of the road while he was playing.

“I feel fortunate. I feel proud of myself. I’ve tried to stay healthy all my life, tried to do the right things,” Aaron said.

His parents willed him a long life. His father, Herbert, lived to the age of 89. Estella, his mother, made it to 96.

“I wish I knew (the secret to longevity),” he said. “Even when I played baseball, I always felt like I had to take care of myself. If I felt like the night before I stayed out a little later and it kept me from playing the kind of baseball I wanted to play, then nobody had to tell me the next night — or the next two weeks — that I had to get to bed.”

On birthdays past

There was nobody doing portraits of Aaron when he grew up in Mobile, Ala., the third of a shipyard worker’s eight children.

Birthday parties were for other kids. Aaron cannot recall any single birthday present from his childhood that left an impression.

There is a sort of pride when he speaks about the humbleness of his background, a wry humor when he declares, “I tell a lot of people I was a vegetarian before they knew what a vegetarian was. We didn’t eat meat but once every two or three weeks.”

He never played high school baseball. Certainly never came up playing any kind of organized youth baseball. When he left home to prove himself in the now-long-defunct Negro Leagues, he held the bat wrong (cross-handed) and contradicted his athletic ability by running on his heels rather than his toes. Such a baseball upbringing is unlikely to be duplicated in the ever-refined future.

On the Braves’ move

A portion of the wall over which Aaron launched the ball that broke Babe Ruth’s revered record stands a lonely watch in a parking lot across the street from Turner Field. That’s pretty much all that’s left of Atlanta-Fulton County Stadium, a faint echo of Aaron’s past.

A prerogative of age is an almost instinctual resistance to change. He said he shed a tear when the old stadium was imploded. He’ll be saddened as well when the Braves bug out of Turner Field for their new suburban Elysium.

“I never played baseball in that park, but it seems I’m connected to it somehow,” Aaron said.

“You have people come along, a younger generation, who have no (sense of) history, no care about what happened there. That stadium should always be (at its current site), I think.” As for the preserved section of Atlanta-Fulton County Stadium, the relic from the historic night of April 8, 1974, when Aaron passed Ruth? “I don’t know what’s going to happen to that little wall. Might end up in somebody’s living room,” he said.

Burden of No. 715

Letters that deserved no more than the flame of the fireplace or the muck of the landfill are boxed in Aaron’s attic. He kept some of the good ones, too, the ones that urged him up and over Ruth’s record.

The vile and racist scrawl sent him in the 1970s, the death threats, that is the indelible stain on Aaron’s story. He would hit 40 more home runs in his professional denouement, but it was No. 715 that extruded the best and worst from the era.

Not that Aaron even glances at any of the old correspondence anymore. He just can’t throw it out.

Forty years removed from the moment, Aaron still wishes he could have savored it more.

“The hardest thing I went through was the fact I was so isolated. I didn’t go out to dinner. My kids had to go to a private school. I had to slip out of the back door of ballparks.

“My teammates would stay in one hotel, and I would stay in another one. Paul Casanova was a catcher with the Braves at the time. After we’d play a night game he would have to bring my dinner to my hotel if I wanted to eat anything.” Where others in search of one benchmark or another may have enjoyed the chase, Aaron looks back on the build-up to 715 and says, “I had no great moments.”

Aaron’s legacy

Note to the generations of fans who never witnessed Aaron in a uniform: He did more than hit a baseball into the seats. He ranks third all-time in number of hits. First in RBIs, extra-base hits and total bases. Fourth in runs. Had three Gold Gloves.

The numbers, though, start to lose their sharp edge over the decades. Stats are incomplete measures of a life, cold figures telling a two-dimensional tale. They don’t, for instance, account for his children’s charity — the Chasing the Dream Foundation — in which Aaron takes such pride.

They don’t make him smile like his five grandchildren and his one great-grandchild. “I have a granddaughter now who’s at Michigan, and I told my wife, ‘Wouldn’t it be nice for me if I can hang around here for four more years to see her graduate?’” he said.

Aaron chased down a record compiled when those of his skin tone could not step foot on a major league field. And in the process shined a light on the dark alcoves of ignorance. What number can express that? “I think overall my life has been good, and God has been good to me. I’ve tried to live my life, in spite of some things that may have happened a few years ago, by doing unto others as I’d have them do unto me,” Aaron said.